When we moved to Muleshoe in 1980, I joined Beta Sigma Phi sorority. At that time the sorority’s big fundraiser was a community bingo night. Sorority members visited local businesses requesting items to be donated for the bingo prizes. One of the merchants on my list was Cliff Allen. So I went to his saddle shop, introduced myself, explained what I was there for, and asked if he would like to donate something for a prize. He thought for a minute, and then said, “ Well, how ‘bout a plyr skberd?

At least that’s what I thought I heard. “Excuse me? What?”

“Plyr skberd! Plyr skberd!” he said again. He shook his head, rolled his eyes, and in exasperation, slapped his hip, and produced a pair of pliers out of its leather scabbard he had made.

A new plier scabbard was the prize he donated.

Cliff is no longer with us, nor is the saddle shop, but the other day I came across a long lost article I had written about him back in the 80s, I think, when I first thought I wanted to be a writer. That attempt didn’t go anywhere, but now I have a platform on which to publish that interview. I have no idea exactly when we talked and I wrote this, so step back in time for a moment and remember Cliff, or make a new friend as you get to know him. Here we go:

**********

“Clifton B. Allen, Custom Saddle Maker, est. 1976” is what the sign states; straight-forward and unpretentious, just like the building it marks. And how fitting, because the man the sign announces is equally straight-forward and unpretentious, a man who could slip into an earlier, simpler period of history where building trust, taking pride in quality workmanship, and accepting hard labor were more evident in the work ethic. He could also fit into this period of history because he has chosen to carry on a skilled craft that harks back to those simpler times- making a saddle from scratch that a cowboy could feel confident would carry him safely through his cowboy chores, be comfortable, and look good.

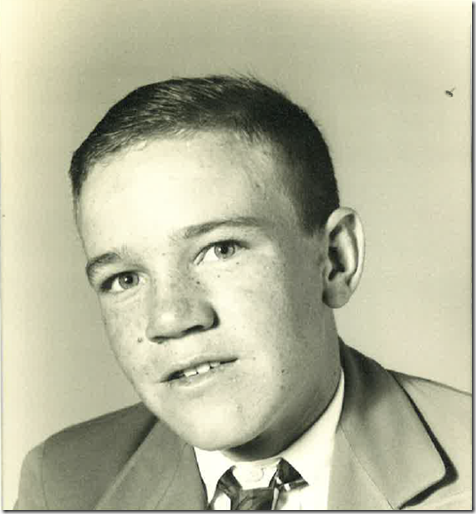

Photo courtesy of Judy Watson

Cliff Allen is a friendly, compactly-built, short man who has never met a stranger. His strawberry blond hair, what is left of it, is graying and blends into his short beard, which is neatly trimmed, but not too thick. His booming voice, which has probably been with him all his life, also responds to making itself heard over the tractor/trailer rigs which pass by the shop regularly on Highway 84 which cuts through Muleshoe, Texas, and which makes it extra noisy since the door to the shop stays propped back and open to invite in the customers and an occasional breeze. The day I spoke with Cliff he was wearing well-worn blue jeans, a western style shirt, a metal tape measurer clipped to his jeans, and suspenders advertising Acme Boots. He also had on running shoes rather than boots. I asked him if he used them for running or jogging.

“I run every morning down to the park and then to Target (an early convenience store) for a paper. I like to keep up with the obituaries and baseball.” The blue eyes twinkled. “I don’t want to miss a friend’s funeral, like I did one time and got in trouble, and I love baseball.”

I asked him why he chose saddle making as a career.

He collected his thoughts as he continued to slice slivers of leather from the headstall he was working on. “Nearly every cowboy at one time or other toys with the idea of making their own [saddle], and I did just that. I was workin’ on the self-taught method and that’s the worst way. Why, I spent enough on that saddle to have gone to Bob Marrs in Amarillo and had a custom saddle made. He’s the person I learned the most from, “ he interjected. “Took me about a year and a half. I was either saving my money to buy leather or trying figure out how I was going to do what I wanted to do.”

Was it a good saddle, a comfortable riding saddle? The eyebrows went up emphatically, “No!”

How does one learn to make a good riding saddle, then? Well, one starts out by enrolling in saddle school in September of 1974 at Texas State Technical Institute in Amarillo and then apprenticing with the aforementioned Bob Marrs at Stockman’s Saddle Shop for two and a half years.

Was the apprenticeship necessary?

“If you had enough money you could stay in school and not apprentice.” He leans over for emphasis, “But if you had that much money, you wouldn’t be makin’ saddles!”

He goes on. “TSTI is almost exclusively preserving the craft of saddle making because in today’s economy, saddle makers don’t have time to make saddles and teach [others interested in saddle-making]. TSTI may soon no longer exist because the school is not paying the government back in the form of income tax [from successful former saddle-making students]. Lots of deadbeats got into it and then found out how much work was involved. If you are really gonna learn, the thing to do is start in school and then go into a shop where a wide variety of jobs come in. If everybody wanted to the same type of saddle, there would be no need for this type of shop, except maybe for repair.”

After his apprenticeship, Cliff moved to Muleshoe to his present location where he lives behind his shop. He started from scratch and did not buy out an established location, an action that he says “has merit, because people know you are there. Otherwise, you have to advertise and you don’t have money coming in yet to spend on advertising.”

I didn’t see Cliff’s shop when it opened in 1976, but it could not have changed much except for the hardwood floor becoming more worn and sanded by the boots of many customers, and odds and ends piling up here and there. It has a 1950’s feel to it. There is no air conditioning, hence the always-open door, and for cold West Texas winters, there is a wall furnace. Four rows of wooden racks display saddles of all types to either be sold of repaired. Shelves hold various materials needed by cowboy types: horse brushes, ropes, saddle blankets, tins of saddle soap, cans of neatsfoot oil, and other horse paraphernalia. Another wall holds headstalls, chaps, belts, halters, lead ropes, barrel racing bats, girts, and reins. A third wall has smaller items on shelves and pictures of saddles made by Cliff. A glass display case has spurs, belt buckles, and bits. Behind the counter is a rodeo calendar, several fiddling trophies, and photographs of his children when they were younger. A barbed wire collection hangs above the upright Coke machine by the front door, always full of icy cold short Coke bottles. The key always seemed to be in the machine for people to open it and help themselves.

The most interesting thing in the shop, however, is the equipment used in the saddle making. Two heavy-duty sewing machines stand out. Cliff calls them saddle stitchers and says they have to have the ability to move leather that has wool skin on the bottom. The machines have a ‘live needle’ that moves forward and backward which moves the leather. The live needle actually moves it along, but it is the combination of the live needle and the ‘walking dog’ underneath the leather that moves the material. A small barrel cut in half and lying on its side with a grating over the top is used for oiling leather and catching the drips. A small square work block with a granite top provides a good cutting surface for tooling and skiving. Tooling is putting the designs in the leather and skiving is beveling the edge of the leather to make it feather thin.

The heart of the shop is a long workbench. Attached to the wall above the bench are the saddle maker’s tools, all neatly held in place, appropriately, by simple strips of leather nailed to the wall in such a way as to create a loop in which to drop each tool; tools which Cliff collected and gathered himself, no mean feat, since some of them are no longer produced for saddle makers. Cans of oils dyes, glues and treatments line the back of the bench top. which is white polyethylene, the same material used in butchers’ shops because of its resiliency to a cutting blade. This is the place where the leather is cut and shaped, measured and glued. On a bottom shelf are piles of scrap leather. A radio with a tape deck also takes up space on this bench, a hint of another passion of Cliff’s: country music.

Cliff was once asked to play rhythm guitar to friend John Fried’s fiddle. “John would do anything to keep me interested, so he taught me how to fiddle. I prefer the fiddlin’. That gi’ tar playin’ is hard on your fingers.”

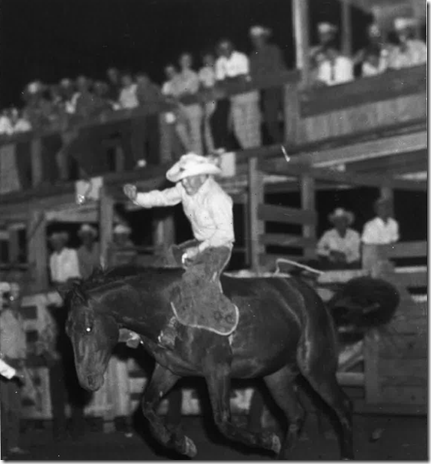

Photo courtesy of Winston Allen

He was pretty good at it, too, winning contests and playing for dances held at the American Legion Hall in Muleshoe.

Who is his favorite composer? “Humph! That’s easy. Bob Wills.” Favorite song? “Faded Love.”

Cliff Allen was born in Dickens County, near the town of McAdoo, Texas, where his father and uncles worked as teamsters for the railroad, pooling their money to buy a farm. They raised wheat, milo, and cotton and ran a few head of cattle. Cliff’s dad and mom eventually bought a farm in Muleshoe and moved there in 1952 when Cliff was twelve. As a teenager he worked on ranches in the area, the Mashed O ranch at Earth, the Mallet ranch in Sundown, even the old U-Bar Muleshoe ranch and the Janes ranch. He also was a feed lot cowboy for King Feed Lot, now Frontera Feedyard. I asked him if he still liked to ride, since he had done so much work-related riding. “Yes, but just for fun. I’m not fixin’ to knock some cowboy out of a job.”

Photo courtesy of Winston Allen

What about other hobbies or interests? He can do a fair job of carpentry work and there is the fiddlin’, of course, and hunting. “I load my own shells, as anybody does now days who hunts very much.”

There was a brief stint with karate, and the jogging. He checks out his tummy and grins, “You wouldn’t believe it to look at me that I do spend a good deal of time workin’ on my weight!”

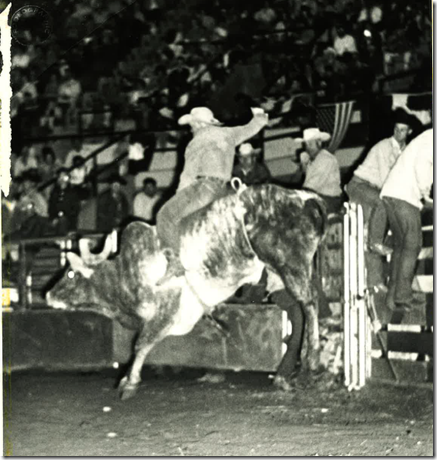

He also goes to rodeos. “I hate cuttin’ contests; they are so boring. Ropin’ is too repetitious. Watchin’ the saddle broncs, now that’s why I go.” He nods his head, satisfied. (Turns out Cliff also competed in rodeos as a young man before marrying and starting a family . He rode the saddle broncs, bareback broncs, and a few bulls and won belt buckles and saddles, some in Earth rodeos. Son Winston still has a buckle and one of the saddles he won.)

Photo courtesy of Winston Allen

Photo courtesy of Winston Allen

But back to the saddle making-what is the hardest part of making a saddle?

“Fittin’ the seat leather and drawin’ on the floral design. That’s the hardest part and you start with that.”

As he goes on, he begins to sound like a teacher of saddle making, a trait that peeks through much of his conversation. “You could put saddle-making into two categories: fittin’ the leather to the tree and then puttin’ on designs; floral design carving or geometric stamping, the basket weave pattern. I could teach a monkey to do a basket weave.”

The eyes show a certain amount of disdain for that process. “All it takes is discipline to stand there and do it. You just set the tool and pound. Gives you a terrible headache! The floral is much, much, much harder. It requires a bunch of tools that you can use. You stamp those, but you’ve got to know how to put them together. In basket weave, you use one tool and another for the border. You use as many as twenty for the floral.”

The wooden saddle tree is the foundation of a good saddle, and I ask Cliff about that. “My saddle trees are made by Redder Saddle Tree Company, El Paso, Texas. I don’t make my own because of the time involved. I can buy better trees than I can make. Tree-making is a vocational skill in itself.”

He settles in with the task of giving me all the details about wood used for the trees. He is teaching again. “The trees are made of lodgepole pine, a medium hard and dry white-colored pine. It grows near the timberline of the mountains where the water leaves early in the spring when the snow melts, and that’s why the wood is dry. The water has left earlier. Indians used this pine for teepees. They put buffalo hides over it and found that this wood retained its original shape even under the weight of the hides. This is what attracted tree makers. You don’t want it [the saddle tree] to warp. You want a tree that is rawhide-covered, rawhide being untanned steer hide. If it is plastic-covered, you can keep the damn thing! They came out with a patented plastic called ralide, made it sound like rawhide on purpose so they could fool a customer.”

The ever-present chewing gum pops as he chews and gets worked up about plastic trees. “A tree out of that ain’t worth a damn, either. A tree is made out of one piece of wood so you can get cross-graining to enhance the strength of the swell and cantle.”

It takes Cliff fifty to sixty hours of labor to make his basic saddle without the tooling and then, depending how fancy and elaborate the customer wants the tooling design, an additional fifteen to eighteen hours are needed for the basket weave, twenty or more hours for the basic floral carve and up to thirty-five hours for the oak leaf and acorn design.

“I do make my own front cinches, and cover my own stirrups, which is a slow job. I do my own latigo tie straps, which have to be oiled since they rub against the sweaty horse and would rot in that salty perspiration. I make my own flank cinches and front cinches. Just covering the stirrups takes a full half-day or more. It’s a tedious job fittin’ the leather to the stirrup. I’ve had saddle makers tell me they can make a saddle in thirty hours! They damn well can’t do it!”

Photo courtesy of Winston Allen

The chewing gum snaps and pops again, and the voice rises with conviction along with the truck noise from outside. “Why, it takes me that long to make those accessories. You cannot buy anything close to the quality of what I do in a mass-produced saddle,” he says emphatically and with a great deal of pride. “The factories can never produce the quality a cowboy needs for safety.”

And just what kind of money does a saddle-maker make for that kind of quality workmanship and safety? That basic fifty to sixty hour saddle with very little tooling would run $1200.00. A comparable factory-made saddle would cost around $800.00, and while it might be slightly fancier-looking, it would not be of the same quality structurally. And from there, naturally, the sky is the limit. Cliff’s most expensive saddle to date has been a cowboy type, single color dye with eleven silver mountings and silver-laced rope effect on the cantle (seat) that set its owner back $2360.00.

That kind of order is not, however, the mainstay of Cliff’s business. He does make anywhere from twelve to twenty-four saddles a year, thirty-four orders in one year being his record. Most of his time is spent repairing saddles and other tack as well as numerous baseball gloves, belts, and occasionally trampolines. “The thing I don’t like about repair jobs on saddles is that they are so nasty. Man, you get grease all over you.”

He does not work on shoes or make boots at all. “Boot-making is hard on your hands. It’s a young man’s game.”

He also takes custom orders requested for other horse or cowboy gear and keeps an inventory of headstalls, latigos, reins, front cinches, breast collars, spur straps, hobbles, chaps, all made by him, on hand for customers who might need something fast.

Walking into a saddle shop is always a pleasant sensory experience, for me, anyway, because of the smell of the leather, a familiar, good smell. I ask Cliff what it is about the leather that makes it smell so good. As I expected, it is not the leather at all, which really has no smell, but the tannic acid, neatsfoot oil, and dyes mixed with the leather that produce the pleasant aroma.

“Neatsfoot oil is made from boiled animals’ feet; cows, sheep, goats. It’s an animal by-product, as is the leather itself.” Cliff the teacher again. “I heard it was deer feet. Hell, where you gonna get that many deer feet? There’s not enough deer in the North American continent!”

He seems at once both tickled and perturbed that people would believe everything they hear.

Cliff obviously enjoys his line of work. Would he recommend it to others?

“It’s hard to stay in business. It’s hard to prove you can make a good saddle better than the mass-produced saddles at the western wear stores. The principle reason is your life and limb. I make an extremely strong saddle. Last repair job I did had been repaired before me by a shade tree saddle-maker and the owner roped a cow and the saddle was jerked apart and torn off the horse. Fortunately, the man was not injured, but this is what a well-made saddle prevents.”

“You’ve got to build trust with the cowboy,” Cliff goes on.

Since saddles go on a horse, a saddle maker pretty well needs to know about horses. “There was this one saddle-maker who was afraid of horses. Made good saddles, but he finally became a boot maker because they [cowboys] couldn’t trust him. He just didn’t speak the cowboy language.”

They did not trust this man because his horse knowledge did not ring true. Cliff’s obviously does.

To recommend to someone the business (many would say art) of saddle making would also depend on the geographic location. Is there a market for the saddle maker to fill? And is the person willing to do the hard work that goes with it? “If they don’t mind the hard work, then yeah, they’d love saddle making.”

I suspect another element of the saddle business that appeals to Cliff is the social aspect of meeting and visiting with the people who come in. The shop, located on the main highway through town, gets some droppers-in as well as serious customers. He enjoys the talk and the swapping of tales, and has a story or anecdote on a variety of subjects.

“I have developed this bad habit of analyzing customers-trying to decide what their motivation was for stopping. Most people don’t have an opportunity to meet people like I do,” he says. “I don’t worry about people stealing. My customers are honest.”

To prove that theory, there have been many times when Cliff has left the shop door propped open and dodged traffic to cross the highway for a visit and a cup of coffee at the café, the Corral, across the highway, and then wander back over when someone drives up.

About that time footsteps are heard on the wooden floor and a tall, slender man in work jeans comes in. After pleasantries are exchanged, business is conducted. “Pardner, you owe me about $50.00. Won’t make you mortgage the farm,’ Cliff says as he hands the man a pair of repaired chaps.

“Well, that’s good, because that farm ain’t worth nothin’,” the man responds amicably.

A typical exchange of friendliness and business on a typical day in a very untypical shop happily tended to by an untypical person, Clifton B. Allen, custom-made man.

**********

Cliff died April 13, 1998, at the age of 59. He was taking his morning run, or maybe a walk by then, for coffee and the newspaper when his heart failed him. The saddle shop is gone; United Supermarkets now stands in its place. The Corral across the highway where he went for coffee breaks is now Leal’s. TSTI did discontinue saddle making courses in 1989, as predicted by Cliff, and the art of saddle- making is sadly disappearing.. Cliff has not been replaced, but Wayne Dendy has opened The Leather Shop on the highway for saddle repair, so the tradition continues in modified form.

Wayne, who had met Cliff and knew his work, said he could recognize a saddle made by Cliff by its distinctive style and workmanship. I feel certain Cliff’s saddles are still being ridden and appreciated to this day.

I caught daughter Shelly at the shop soon after Cliff died, and she graciously let me come home with this rub stick and mallet he used all the time on his saddles. I wonder if this rub stick was a tool he might have made himself to smooth leather and work in corners where leather comes together. The mallet was for smoothing stitching on the leather and for tooling those patterns that decorated the finished saddle.

And that plier scabbard that first introduced me to Cliff? I don’t wear it on my belt like he did, but it has its own special place in my barn, the pliers always handy when I need them.

So with my apologies to Bob Wills: Cliff, your memory has not faded, because I can remember you when I use these pliers.

Thanks to Winston Allen, Shelly Allen, Wayne Dendy, Gina Wilkerson, Rhonda Carpenter, Judy Watson, and Jim Blain at Panhandle Leather for their help with this story.

This is a great account of my dad’s business and life. Even though I had to wipe the tears away as I read it I want to thank you for writing it.

You are very welcome, Winston. I had a good time writing it and remembering your dad.

Great story about Clifton. I knew him from all the Allen, Brownlow reinions.

Thank you! I had a good time writing that story.

I still have my plier scabbard stuffed in a desk drawer. It is well worn but still holds together. My Dad gave it to me.

I used mine from Cliff just this afternoon!

Takes me back to a simpler, much happier time in my life when my Daddy was still here. You captured so much of his little quirks, thank you. He was the best!

You are welcome, Shelly. It was my pleasure to write it.

I am in tears. Uncle Cliff was a very special man. My ex actually painted the sign for his shop when he first started. There are so many memories of him. I vaguely remember his rodeo days, and working at the feedlots…love and miss him dearly

Didn’t mean to make you cry, Norma! But I am glad the memories touched your heart.

Glad you were able to find the photo! Enjoyable article.

Thanks, Rhonda. It’s a great photo.

Cliff was great man Ed and I thought a lot of him. I did know he did all of the things he did like playing the fiddle. I knew he had a saddle shop.Ed loved visiting with him. He was my brother in law

Thanks for reading the story, Wanda.

Wow! That was an awesome read, and a wonderful step back in time. I learned a lot in that saddle shop, and it was men like Cliff Allen that made men out of all the boys that grew up around them.

Thank you for writing and sharing this.

You are welcome, and thanks for reading, Jay.

Oh how I missed going to his shop when I was a kid. I was inspired every time I went and spent time with him. I always thought if there had been a real John Wayne like in the movies this was him. He bought me Moby Dick and Treasure Island when I was old enough to read. I read them both knowing if my parents would have bought them for me I would have used them for a door jam!

I like your comparison of Cliff to John Wayne. And good for him for encouraging you to read!

Thank you for the account. My family were close friends of the Allen’s and their children and we spent a lot of time together – picnics, parades, poker games and threatening tornadoes. Years later I stopped by Clifton’s shop while in town visiting my parents and would return whenever I was in town. Such a genuinely good man. He encouraged me to re-connect with his daughter, Shelly who I had not seen for decades. Her and I remain friends to this very day. Thanks again.

It was my pleasure to write the story.The Garth family was mentioned by Winston when we talked as I was adding to the story. I’ll bet there is a story behind the threatening tornadoes!

Great story I remember that man and I remember seeing him run to target . He was a sweet man . Shelly and Allen this is a story y’all need to treasure . I remember the store also . Mrs Liles you did it again you do an awesome job . ❤️

Thank you, Rosa. I am glad you like the stories.

Great read! I remember Cliff, and going in his shop with my grandad. Also remember him playing the fiddle.

Enjoyed this very much.

Glad you enjoyed reading bout Cliff, Cory.

Hi Alice,

I enjoyed your story so much having grown up on a ranch in the Colorado mountains. In the town that served as the county seat, we had a shop run by a family similar to the one you describe here. For ranch people, the shop served as the center for county news and socializing with other ranchers as they brought in harness and saddles for repair or were picking up the repaired items. As in Muleshoe, the shop no longer exists. Thank you for sharing this experience and providing a touchstone memory for one of the skills being lost.

Alice, I met you at the Vee Bar Guest Ranch quite a few years ago and have looked at your blog off and on through the years. You have done a great job with it and now I need to get your book!

Thanks for your comments, Kaye. I went to the Vee Bar three times and would love to go back. I have stories about those trips on the blog, but they aren’t in the book since it deals with Muleshoe. But they might show up in the next book!

Wow, I came back to reread this article and saw all the comments. Everyone sharing their memories of my Daddy really blessed me. Thank you all for reading about him and sharing your thoughts about him or an experience. I never knew how much I depended on him until the second they told me he had gone to be with God. In that second I knew my world was shattered and my life would never be the same. I was right. I miss him terribly.

I am glad you checked back to read all the comments, Shelly.

Another great read.

Thanks, Sheila.

I never knew Cliff, but I went to TSTI saddlemaking school in 79-81. Reading this brought back so many memories.

Cliff was quite a character! I always enjoyed visiting with him. Thanks for reading and commenting, Ron.

Once again, i sit here reading this holding back the tears!! Thank you, Alice. I am now 59 years old and remembering dad and the saddle shop i grew up in.

I’m so glad the story brings back memories for you, Winston. I think it is one of my best stories, and I enjoyed writing it.