I had a call Friday morning, December 10th, from Ryan Young, publisher of TrojanSports.com, a website devoted to sports coverage for the University of Southern California, requesting a chance to ask a few questions about Lincoln Riley, their new head football coach. Once again, just as I said to Ryan Kartje, the LA Times reporter I had visited with on December 3rd, I would be happy to visit with him, but wasn’t sure there was anything I could tell him that he and most of the football world didn’t already know about Lincoln. Not to worry, Ryan assured me, as he was sure his readers would be interested in anything he could add to the background of Lincoln’s story.

So he came, we talked, and his story reflects what he learned about Lincoln in relation to Muleshoe from me, Stacy Conner, Bob Graves, and Natalie Leal as he visited here in town. Ryan also talked to David Wood by phone.

I have Ryan’s permission to share his story with you, but you can also read it online at his website at TrojanSports.com for a few days for free. The website is a subscription service, but he wanted to make it available to Muleshoe readers initially until it needed to fall back on the subscription requirement. I think you will find it interesting the pictures of town that he took to illustrate the story. I even got to be one of the pictures! What a deal!

Thank you, Ryan, for your impressions of Lincoln and Muleshoe and your willingness to share it. Here we go.

The story of Lincoln Riley’s big rise starts in little Muleshoe, Texas

Muleshoe, Texas, hometown of new USC football coach Lincoln Riley. (Ryan Young/TrojanSports.com)

Ryan Young • TrojanSports

MULESHOE, Texas — Speaking over the phone Friday morning, new USC football coach Lincoln Riley is discussing his adjustment to Los Angeles so far and laughs when asked about his current living arrangement.

“Yeah, hotel right now,” he says. “…. It’s been hectic. I’ll be excited for the dust to settle a little bit where we can get a chance to get to know this place and obviously find a place to live and just kind of really get settled in as members of the community.”

Just a few days into his Trojans tenure, Riley was already on the road recruiting, with stops from Las Vegas to Georgia to Texas. He got back to Los Angeles last Sunday for a big on-campus recruiting event and has been working this week to settle into his new surroundings and meet his team.

“We were out of state a lot the first week trying to get all that recruiting done. This week’s been mostly here locally, obviously doing some recruiting, but spending a lot of time here within the facility, especially with the current players,” he says. “That’s been important to be able to connect with them, spend some time with them, start to be able to evaluate the roster.”

It has now been two weeks since Riley shocked the college football world — and even those who have known him his whole life — by leaving Oklahoma after posting a 55-10 record, four Big 12 championships, three College Football Playoff appearances and two Heisman Trophy winners over five seasons as head coach, to take on the job of rebuilding USC football.

It wasn’t just surprising that one of the most respected rising stars in the profession left one blue-blood program for another but that he did so for Los Angeles, after spending most of his life and career relatively close to home — and in decidedly different settings — in West Texas and Oklahoma.

As Riley noted, he hasn’t had all that much time to get his bearings in L.A. yet, especially considering the conversations with USC about taking the job happened quickly and without an in-person visit to campus.

“The campus is different than I imagined, in a positive way. The campus is amazing. I had this notion in my mind that the Coliseum was going to be way off campus and it’s not. Just some things you maybe thought of because it’s in a big city and really the feel here on campus and around that is not that — it’s a cool little community,” Riley says. “I would just say as strong as I felt about it obviously to take this job and accept it, I would say everything I’ve seen up to this point confirms that or even makes me feel stronger about it. It’s the right place.”

Outside of the USC and Oklahoma fan bases, which have reacted to Riley’s move to the West Coast with wholly different but equally intense sentiments, the news has probably created the most buzz within a small town in West Texas, right on the edge of New Mexico, that raised Riley and set him on this path in the first place.

Muleshoe, Texas, is a town of just over 5,000 people with one stoplight and expansive farmland surrounding it from every side. Dairy, cotton and other agricultural industries drive the local economy, which like many towns and cities across the country has been impacted by the pandemic and the resulting toll on small businesses.

As its proud citizens will say, though, Muleshoe is a tight-knit community that supports one another, that has a strong investment in its school system and raising its next generation and that cares deeply about football.

So, yes, in this small town 85 miles southwest of Amarillo and 68 miles northwest of Lubbock, USC’s coaching hire has been a big deal.

“There was a lot of conversation — a lot of conversation,” says Stacy Conner, pastor of the First Baptist Church in Muleshoe. “… We had dinner with friends [that] Sunday night and that was the first thing that came up — ‘Did you all see?'”

“It was a shock to us,” says Alice Liles, who was Riley’s English teacher his 11th grade year at Muleshoe High School.

But not in the way it was in Norman, Okla. No, Muleshoe will always feel a strong attachment to Riley, because no matter how far he gets from his roots geographically there’s a deeper connection shared by both the town and its most famous native son that has always transcended college football loyalties.

“A lot of people will tell you we’re fans of our school and wherever Lincoln is, so come next fall at Leal’s [Mexican restaurant] you may see some USC shirts that you’ve never seen before. It wouldn’t surprise me at all,” Conner says.

Speaking on the phone Friday with a reporter who had made the trek to Muleshoe, Riley said, “Tell everybody I said hello.”

He might not get back as often now as he used to, since his parents Mike and Marilyn moved to Lubbock and his grandparents passed away in recent years, but wherever Riley’s career has taken him, his story can’t truly be told without starting here.

“I used to get back a couple times a year. I probably won’t be through there quite as much as I used to be without family ties there, but it will obviously always be home,” he says.

Before the call ends, as Riley has to get back to work Friday preparing for a pivotal weekend hosting recruits just days before the early signing period, he’s asked if he has any recommendations for a first-time visitor.

“Definitely go eat at Leal’s — don’t miss that,” he says.

Leal’s Mexican restaurant has been a staple of the Muleshoe community since 1957. (Ryan Young/TrojanSports.com)

‘It’s kind of one of those — the village kind of raises you.’

It doesn’t take more than a half hour after Leal’s opens its doors at 11 a.m. Saturday before the parking lot has filled up, with the front door swinging open seemingly every other minute with more diners or those coming in for pickup orders.

The popular Mexican restaurant has been a staple of the community since 1957 and in its current location since about 1993, across from the United supermarket, in front of the train tracks and next to an old but still in-service grain elevator. (A couple times a day the train rumbles by, rattling the walls.)

A third generation of the Leal family (pronounced Lee-al) is now involved in the business, which started out with a tortilla factory in Muleshoe opened by Jesse and Irma Leal, then a little cafe at the end of town and now with the current location in central Muleshoe as well as restaurants in Lubbock; Plainview, Texas; and nearby Clovis, N.M.

Cowboy hats line the top border of the walls — a tradition that started around the time the current location opened in the early 1990s when one gentleman gave his hat to the cause, signing his name to it, and setting the tradition that dozens of other cowboys/ranchers have since followed.

Talk to anybody in Muleshoe and they’re likely to recommend a trip to Leal’s, just like Riley did — and deservedly so.

Liles, the former Muleshoe High School English teacher, joked that when the restaurant was closed for a few days recently it set in a panic among locals who were thrown off their routine in having to find a different place to eat.

“We’re a part of Muleshoe. Muleshoe’s a part of us,” says Natalie Leal, whose grandparents started the business and who now manages this location. “It’s small and tiny, but you know what you’re going to get when you come in. There’s never a dull moment. It’s just always constant.”

Natalie Leal pictured in front of a wall of family photos inside Leal’s Mexican restaurant. Below, the cowboy hats adorning the restaurant became a tradition in the early 1990s. (Ryan Young/TrojanSports.com)

Natalie Leal is the same age as Riley and was his classmate from kindergarten through high school. She’s not necessarily a passionate college football fan, but she took in the news just like everybody else a couple weeks ago.

“People were talking about it,” she says.

She had left Muleshoe in 2011 to run the family’s restaurant in Amarillo, which was ultimately a casualty of the pandemic, and moved back recently to manage this location. But even up in Amarillo there was support for Riley’s career, regardless of the more general rooting interests in the region.

“When we were in Amarillo we got OU cups to support him and stuff and we had people come in like ‘I’m not drinking out of this.’ And it was like, ‘We’re supporting Lincoln — Muleshoe forever,'” she says.

Natalie Leal hasn’t seen Riley in probably 20 years, she says. She left town just like he moved on with his career, but they had been classmates from the start and, as she recalls, their senior class was a little more than 70 students, so there will always be a familiar connection there.

“He was always just the buddy. You just knew if Lincoln was around, everything was safe, everything was going to get taken care of. So smart. He’s just always been that way,” she says. “… Even though it’s been years that we haven’t seen each other, you just know it’s always, you’ll pick up where you left off.”

That goes back to the general sense of community felt in Muleshoe. It’s a point of pride for the residents — some whose parents and grandparents established roots here, like Riley’s, and others who moved in decades ago and never left, like Conner and Liles.

“The community, it’s so tight knit,” Leal says. “To be able to be back like nothing has changed — the houses aren’t as new anymore, the paint’s not fresh, but you still know, ‘Yup, Mrs. Thompson still lives there, been there for 60 years.’ And that’s everywhere.”

Conner, the pastor, was raised outside of Lubbock but is coming up on 31 years in Muleshoe. He had offers to take larger pulpits at times, but his kids were still in school and he and his wife Debbie — who was one of Riley’s math teachers in high school — made the decision to keep their children in the structure that Muleshoe offers.

“For us, this has been a good place,” he says. “This town has invested in a life of children. They are supportive of the school system, they’re supportive of one another’s kids. There’s just a sense of community, of welcomeness here that you might be able to find other places but it seems to be in the DNA of this town — to support one another, take care of one another.”

Conner is in his office Friday afternoon after just finishing the funeral for a 95-year-old Muleshoe woman. He says 250 people were there to pay their respects, which speaks to that sense of community here.

“If I go to Lubbock and do a funeral for a 95-year-old, there’s 40 people, 30 people gathered in the chapel,” he says.

“As far as the town goes, it’s just a good hard-working farming town. They raise cotton around there and there’s a lot of dairies. They’re just hard workers,” former Muleshoe HS football coach David Wood says.

Liles, meanwhile, welcomes a visitor into her home Friday afternoon after she too had returned from the funeral. She’s retired as a teacher now, but like Conner, she relocated to Muleshoe decades ago and never saw a reason to leave. It was back in 1980 when she got the job offer and she and her husband Bill decided to move from Edna, down on the Gulf Coast of Texas.

“Bill came up here [before me] and he laughed, he said, ‘They told me the only time you have to lock your car up there is in the summer so people won’t put extra squash and okra and stuff in your backseat,'” she jokes.

As for the name of the town, which was founded in 1913 when the Pecos and Northern Texas Railway built an 88-mile line from Farwell to Lubbock, well there’s a couple stories that have been told over the years.

“The story that I’ve been told and I think is in the Bailey County history over there is this was a line camp of the XIT Ranch out of Dalhart — it’s 100 miles to Dalhart and the ranch stretched well past here — and they branded with a muleshoe at that line camp. And when it came time to name it they just went after the brand, muleshoe. That’s what I’ve been told,” Conner says. “There’s another story that supposedly settlers were here and they were building a house and they dug up and found a muleshoe in the dirt and that’s how it became Muleshoe. I don’t have a clue what’s right.”

Regardless, this is where Riley’s story begins — years before he started rising up the ranks as one of the top coaches in all of college football, making national headlines from coast to coast with his career moves, etc.

And those that have followed him on this journey from the start have a palpable pride to them as they gladly share stories and perspective on the Trojans’ new head coach.

Even if many haven’t seen him in a while, as his past visits back to town were often tied around family or a quick opportunity to pop into the old Muleshoe football office while traveling on recruiting trips.

“You might stumble into him every now and then at Leal’s after he graduated from Tech, but not very often,” Conner says.

Still, the stories are shared as if they happened yesterday.

Meanwhile, back on the other end of the phone in Los Angeles, as Riley takes a quick break to reflect on such things amidst another busy day with recruits traveling in from across the country to visit campus, it indeed feels like the sentiments are mutual.

“I think it was just kind of your typical small town. Everybody knew everybody. A lot of good, very hard-working people out there, and I think most of us were kind of shaped that way,” he says. “Very strong sense of community, very tight-knit community, people watched out for each other. There wasn’t many secrets. Everybody kind of knows everybody and it’s kind of one of those, the village kind of raises you.”

‘We are a football town. We’re in Texas, and football’s a big deal.’

Wood came to Muleshoe High School in 1996 to take over a struggling football program. He was working at a bigger school, Randall HS in Amarillo, but this was an opportunity for his first head coaching job and he couldn’t pass it up.

“When I first got there, football was not very high on the totem pole,” says Wood, who retired after the 2017 season. “They had very few winning seasons in the history of the school, and it had been a while since they’d even had a winning season let alone a playoff run or anything like that. It was a risk for me too, but it was my first head job and you don’t get to pick and choose when it’s your first head job.”

Having grown up in a football family — his grandfather Claude Riley (who lived to be 100 before passing away in Oct. 2020) had played quarterback on Muleshoe High School’s 1938 undefeated team, his father Mike Riley later played QB at the HS, Lincoln eventually became the QB there and his younger brother Garrett Riley (now the offensive coordinator at TCU) would later man the position as well — Riley knew the recent struggles of the program and saw how the town was responding to the newfound success Wood brought.

“It was probably the worst program in the state of Texas for years and years. Coach Wood and his staff came in, they really turned it around and I think the fans, the parents, the community as a whole was very eager for it,” Riley says. “They hadn’t had success in so long and when we started having success the town just rallied and it really I think became a point of pride for the entire town.”

Just as Riley is now being tasked to “change the culture” at USC, as is the popular phrase, Wood was in much the same situation walking into Muleshoe HS in 1996. He knew he had to change the entire way the kids and the town looked at football, but he didn’t know quite how that would go over.

“When I first got there, I had a superintendent that said, ‘If you’re going to do this, what you’re talking about, then you’re going to take some bumps and bruises along the way. They’re not going to appreciate some of the changes you’re going to make.’ I said, ‘Well, are you?’ He said, ‘I’ll have your back and so will the administration,'” Wood recalls. “Those kids were used to doing whatever they wanted to do — that’s why they never won. The parents would always back the kids.”

Wood went 1-9 his first year and 5-5 his second year before things really took off.

“We didn’t have a losing season the second season and they hadn’t seen a non-losing season in I don’t know, it was forever — 15, 16, 17 years, I can’t remember exactly. The next year we went 10-2 and won a playoff game and that was neat. The town just exploded with pride,” he says over the phone from Crowell, Texas, about three hours east of Muleshoe where he has since relocated since retiring after 19 playoff appearances and 184 wins over 22 seasons.

“We still weren’t on the map — we weren’t put on the map until Lincoln’s junior year when we went to the semifinals in the state of Texas. And then we were kind of put on the map football-wise in the state of Texas.”

Riley had hoped to compete for the starting quarterback job his sophomore year, but he dislocated his shoulder in practice and would instead start at defensive end while wearing a shoulder brace all season.

Truth be told, he never fully recovered from that injury, but his arm was good enough to take the reins of the offense as a junior.

Muleshoe had some big offensive linemen that year — which they never quite had again, Wood says — and Riley was the leader of the offense, but the team also utilized a senior running QB.

“Lincoln never batted an eye when we said, ‘Let’s put the running quarterback in and let him do some things for a series and change the tempo for the game.’ He never once questioned it. That’s just him — he was a leader that way,” Wood says.

Muleshoe went 14-1 and reached the state semifinals during that 2000 season. A large sign commemorating that team stands prominently outside the school’s stadium.

Without the same size along the offensive line the next year, Muleshoe didn’t have quite the same season, but the program was now on its way and would win a Class AA state championship in 2008, with a large contingent of supporters making the trek to Dallas for the title game.

To this day Muleshoe is known for traveling large crowds — 2,000 to 3,000 fans for both road playoff games this year, according to Conner.

“As the years went by the town developed into a football town. It was a priority for them and they were proud of that. The town was proud of it,” Wood says. “… There was a total cultural change. They all bought in, kids, parents, and now that’s what Muleshoe is kind of known for — their football.”

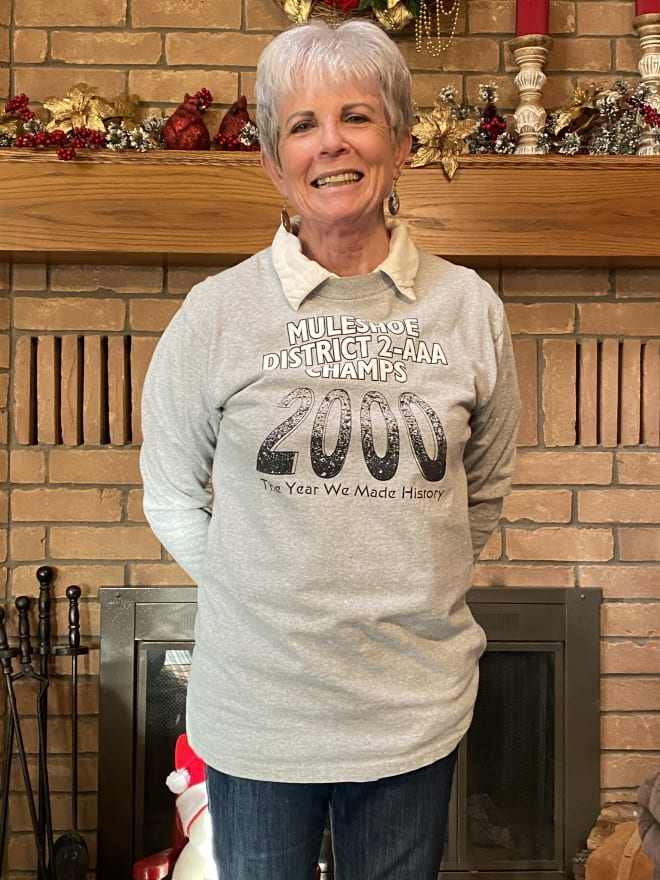

“We are a football town. We’re in Texas and football’s a big deal,” Liles says, wearing the commemorative shirt from that 2000 season. “It’s a thing — you go to the football games even if you don’t have a child playing because that’s just part of the routine.”

Staking claim to one of the most accomplished young coaches in college football has surely only bolstered that identity.

But Wood never expected Riley to go into coaching. He thought he would have too many other opportunities that would pull him toward a different career path.

“He wasn’t a man of a lot of words, he really wasn’t. It was just, for one thing, he’s brilliant, so he never said anything that wasn’t right,” Wood says. “He’s got this uncanny ability to see something and never forget it, photographic memory almost. I don’t know if it’s almost — he may have a true photographic memory. I just know he could watch film with us, and as coaches we sit there and run it back and forth and back and forth. He sees it one time and he’s going to remember it. … So as far as leadership goes, when he said something people knew he knew what he was talking about.

“Even going to college we thought he’d end up being FBI or NASA or something. He was so brilliant. His math skills were unbelievable. So he never did tell us he wanted to be a coach. It just happened so quick.”

After high school, Riley decided to walk-on as a quarterback at Texas Tech in Lubbock. Wood and the other Muleshoe coaches had tried to encourage him to consider taking a scholarship at smaller school where he could make an impact as a player, but Riley wasn’t even interested in having a conversation about it — his decision was made.

Asked Friday why he was so resolute in the decision to go to Texas Tech as a walk-on, he answers matter-of-factly.

“Just to do it big. Just to do it big,” he says. “I did have some other opportunities that were very interesting, but I said, if I’m going to go do it and invest then I want to try to do it at the highest level. Tech represented that for me.”

Says Wood: “He had his mind set. It didn’t work out as far as playing, but everything else in his life worked out because of that decision. He’s got some foresight about him.”

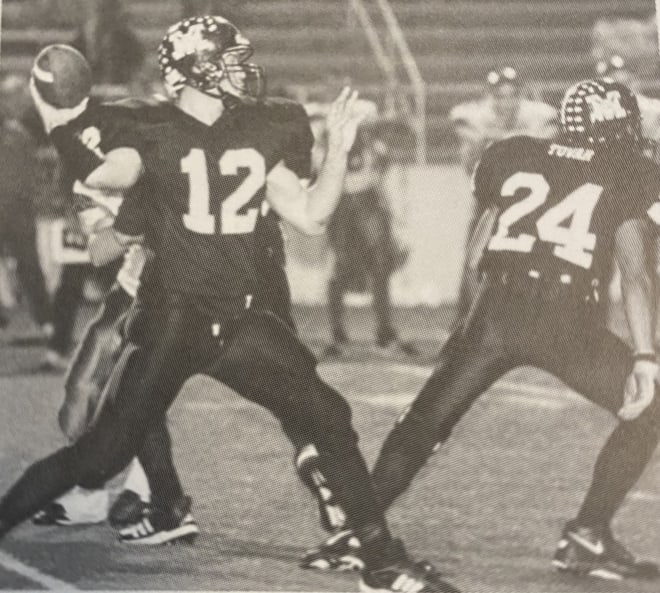

Lincoln Riley quarterbacking Muleshoe High School. (Muleshoe HS yearbook/Courtesy of Alice Liles)

‘We all left and said, ‘He’s going to be a head coach somewhere big.’ We could all tell.’

Wood knew Riley’s shoulder wasn’t going to allow him to play college football at the Power 5 level, but he didn’t know then what that Texas Tech opportunity would lead to for the ambitious quarterback.

“With his shoulder the way it was, we all kind of knew he couldn’t be the guy because he couldn’t really handle it with his arm because it was a pretty bad dislocation. It was never the same — good enough for high school football, no doubt, but to go be a Division I quarterback and do the things they were asking him to do, he couldn’t throw it 60 yards. He could throw it 40-45 pretty good but he couldn’t rear back and throw it. But that never stopped him from believing he could still go to Texas Tech and play,” Wood says.

“And he didn’t. Leach saw that from probably the first week of practice. I think this is the way the story goes, the first week or two of two-a-days he said, ‘You’re not going to probably play here much, but I sure want you to think about being an assistant coach for me.’ Everyone knows the story from there.”

Riley clarifies that it was going into his second year at Texas Tech that then-head coach Mike Leach approached him about segueing into a different role, and it was a true crossroads moment where he had to accept the reality that the earlier shoulder injury had perhaps changed his football course more than he realized.

“It was an interesting time in my life. I walked on at Tech and that was going well. Coach Leach came to me and asked me, gave me an opportunity to kind of start [the coaching] part. He heard that I wanted to potentially coach. I had busted up a shoulder sophomore year of high school that probably changed paths for me a little bit. I’m not saying I would have been some crazy elite recruit or anything like that, but for a quarterback to have your right shoulder pretty shredded was a big deal, especially surgeries at that point hadn’t quite progressed to what they are now,” Riley says, telling the story. “So that changed the path a little bit. There were some limitations I had after that that I knew, so that combined with the opportunity that Mike put in front of me at the time, I just had to start thinking about years and years down the road. I knew it was a pretty unique opportunity, so I jumped on it.”

It was actually Bennie Wylie, who is USC’s new head football strength coach after following Riley from Oklahoma, who pulled him off the field midway through summer workouts and told the walk-on QB that Leach wanted to see him in his office.

“Mike kind of spent a couple hours with me, kind of laying it out, what it would look like, what it could mean. I was a little bit in shock,” Riley recalls. “I took kind of the weekend, I remember, to process, and as much as I didn’t want to stop playing football I kind of had a sense this was a very, very unique opportunity that was going to be tough to pass up.”

While his coaches back at Muleshoe didn’t know that he was seriously thinking about pursuing a coaching career of his own, Riley had already started thinking about it during his first semester at Texas Tech when he had not yet been able to walk-on to the football team and he was just a student.

“The very first semester I was at Tech I didn’t do anything with football, and so that was like the one time in my life after starting ball that I didn’t have it. I knew after a month of not being a part of a team or not kind of having football in my life, I knew I wasn’t going to do that anymore,” he says. “So just a little bit away from the game was enough for me to know.”

So from 2003-05, Riley was a student assistant for the Red Raiders.

“He was Leach’s right-hand man on the sideline because of his memory and his intellect of the game,” Wood says. “He followed Coach Leach around on the sideline and then become a staff member once he graduated. It’s pretty remarkable.”

Riley would get elevated to a graduate assistant role on staff in 2006 before another promotion to coach the wide receivers from 2007-09 and his career would take off in a big way from there. He’d spend five seasons as the offensive coordinator at East Carolina — his only other period outside the Texas-Oklahoma region until now — then join Oklahoma as OC from 2015-16 before taking over as head coach at just 33 years old when Sooners legend Bob Stoops retired.

Wood wasn’t surprised.

While he didn’t initially expect his former QB to go into coaching, he realized very early on in those years as a student assistant that Riley was destined for such heights in the business.

Which leads to another good story …

Leach’s Air Raid offense was drawing significant attention by the early 2000s, and Wood wanted to adopt it at Muleshoe. Especially without the big offensive lineman coming through the program anymore, he liked the wider splits Leach employed on the O-line and how that could suit his personnel.

“We wanted to go learn that. We called Coach Leach up and said, ‘Can we come visit with you one spring? We’re going to change to the spread.’ He said, ‘Sure, come on. Lincoln will be here with me too,'” Wood says. “So the offensive staff went over there and I guess Coach Leach talked for about 5 minutes and then he said, ‘You know what, I’m going to turn this over to Lincoln. He knows more about this offense than I do and he can take you step by step how to install it, what you do during two-a-days, what you emphasize with every play.’ And he left the room and Lincoln just took over and we sat there, I guess, four or five hours and he told us step by step.

“It was unreal the way Lincoln could relay that information to us so that our high school kids could do it. Not dumbing it down because we had to know exactly what was going on, but interpret it for us so that we could portray it to our high school kids without it blowing their minds. We had to make a few phone calls back to him, but to install a whole offense in four hours is pretty amazing.”

A few years later Muleshoe HS rode that offensive system to that 2008 state championship.

Riley downplays the story now.

“What was happening at Tech was very cutting edge at the time and our coaches at Muleshoe were interested in it and I spent some time with those guys sharing some of the things I had learned at Tech. It wasn’t nothing really dramatic — it was just coaches sitting around the room, talking ball and I was giving them some of the things that I learned and I think they ended up taking a thing or two off of that and becoming pretty successful with it,” he says.

It was more than that, Wood reiterates. He knew in that moment what the future held for Riley.

And nothing that has come since has surprised him — well, almost.

“He had it. I could tell he had it when Leach gave us Lincoln to do his offense, we all left and said, ‘He’s going to be a head coach somewhere big.’ We could all tell,” Wood says. “We’d always go visit colleges and the offensive coordinators from different colleges, as high school coaches do — in the spring they have a trip and they go see people. Those colleges will let you have their offensive coordinator there and let him talk a few things — definitely not a whole offense. But after visiting with Lincoln, the way he did it, made it sound so simple, here he is, he’s not the offensive coordinator at the time — he’s an assistant student coach — and he explained things a whole lot better than any offensive coordinators that we would go see. It was amazing.

“I had no doubt what he was capable of, becoming a head coach somewhere big — not just later in his career but early in his career.”

Lincoln Riley, middle, joined by USC Chairman of the Board of Trustees Rick Caruso, USC President Carol Folt and athletic director Mike Bohn at his introductory press conference inside the Coliseum. (Kirby Lee/USA TODAY Images)

‘He doesn’t do anything that’s not calculated. He’s got a plan.’

Bob Graves is another Muleshoe transplant who just never found a reason to leave. He came to town in the fall of 1958, from Hollis, Okla., for a teaching job. He met his wife Billie here, went on to become an assistant principal, principal, coach and later did the Muleshoe football radio broadcasts for 25-30 years with his nephew Ronnie Jones.

He’s also been a diehard Oklahoma fan since 1947 and has the OU logo and the Sooner Schooner painted on opposite ends of the curb at the base of his driveway.

He got a call from his son two Sundays ago making sure he saw the news that Riley — less than a day after answering a question by saying he would not be taking the LSU job — was actually leaving for USC.

“I was really disappointed and shocked,” Graves says while hosting a visitor in his living room. “But Lincoln will do fine. He’s that good a coach. And I think they’re too hard on him in Oklahoma, but it was the way he left. It came up the next day after they’d just lost a tough game to Oklahoma State.”

Like many in Muleshoe, Graves got to know the Riley family well over the years. He coached Mike Riley in middle school and later got to know his boys well. Early in Riley’s time at Oklahoma he called Graves.

“He called me that spring when he took the job and he was on a recruiting trip and he said, ‘I just thought I’d call you and see what you were doing.’ That surprised me and I appreciated that,” he says.

Just as the news Sunday surprised him.

There aren’t a ton of Oklahoma fans in town — there were definitely Riley supporters during his time there but few who follow the program the way Graves has for more than seven decades now. Even still, he feels the Sooners fans are reacting too harshly to Riley.

“It was a shock. It was really a shock that he left so quick, just sudden, and I think that’s one thing that made the people so upset in Oklahoma,” Graves says. “But Lincoln’s a good guy. He’s a good guy, good coach and I think he’ll do good out there. Of course, the money — tremendous contract. He’ll do good. He’s very intelligent, he’s very smart.”

Graves may have felt Riley’s Oklahoma departure in a different way, but again, many in town were just as caught off guard when the news hit.

“To jump from OU all the way to California, that was a shocker and people were surprised. I think my husband came in and told me because he watches Paul Finebaum. It could have been on the computer — I might have seen it on the computer — but yeah, it was a shock,” Liles, Riley’s high school English teacher, says.

“I was in my basement that Sunday afternoon writing an article when my son from Lubbock called and said, ‘Did you see?’ I opened up my phone and there it was on my Google feed that he was going to USC. So nobody knew, and then everybody starts trying to figure out the motivation just like everybody else,” says Conner, the pastor. “You assume it’s for more money, the SEC thing [with Oklahoma set to change conferences]. Everything we think about is just conjecture just like it is with everybody else. I haven’t talked to him, and if I was Lincoln I probably wouldn’t tell anybody because they might put it out there.”

Conner is protective of Riley. A few years back when a writer wanted to do a biography on the Oklahoma coach, and Riley felt it was way too early in his life and career for that, Conner says he and others didn’t talk to the author for it.

This time, he sensed there would be renewed media interest and reached out to the USC sports information office, which told him that indeed two different reporters were planning trips to Muleshoe.

“When this all broke, I figured you guys would come,” he says, warm and welcoming and happy to spend a half hour in this case talking about Riley.

“There is a lot of pride in how Lincoln has done,” Conner says. “When he became the head football coach at OU at [33] that was a real shock, and there’s a lot of OU fans in town that are very proud that this local boy had risen to the very top of the college football world and he’s still there.”

Well, probably more Oklahoma fans after Riley got to Norman.

“Yes, Lincoln is a local hero,” says Liles, who has self-published a book — “The Bright Lights of Muleshoe” — and is considered by some to be a resident historian of the town.

She notes that for a long time the most famous person with a tie to Muleshoe was Lee Horsley, who was on several television shows in the 1980s. Now it’s Riley.

And like Wood, she notes that if it wasn’t football, Riley would have found great success in something else.

“He could have done anything he wanted to do, and this is what he chose to do,” she says.

There are too many stories to share. Stories about the way young kids in town responded to Riley, so that when there was a need to deliver a message and help get some junior high kids to start caring about academics again, that he was the one called in to talk to them because they would listen to him.

But there’s one more anecdote from Conner, whose wife was Riley’s math teacher, that helps paint the picture. It reinforces what Wood said about his former QB and really what everyone who was interviewed for this story said about him.

“Lincoln sees math in different ways than the average student was seeing it at the time. He could sit there and they could go through the textbook and Lincoln knew two or three other ways to get the same solution. He’d keep interrupting Debbie and saying, ‘But there’s another way.’ And she’d say, ‘You’re right, there’s another way, but this is the way we’re teaching everybody else.’ But that gives you some insight into his mind,” Conner says.

“When I did his grandmother [Evelyn Riley’s] funeral service [in 2019], her sons told me the story — she traded cotton in her head. She ran a legal pad on who owned the cotton, who she was buying from and how many bales she bought, but she traded the numbers and the grade in her head, which are incredibly complicated calculations. After visiting with them about the funeral and telling those stories at her funeral, you can see where Lincoln gets some of that mental aspect, probably from his grandmother,. And the backside funny of that is that Mike’s dad, Claude, went into the hospital and had surgery, and while he’s in the hospital having surgery she bought Apple stock. And this was way back in the early 2000s, late 90s. She bought Apple stock and he got out of the hospital and he could not see any reason to buy that stock so he and Mike sold that stock.”

Riley’s coaching stock has been on a similar directly-upward trajectory these last two decades as well, and USC is now banking that will continue, that he can be the blue-chip hire to resurrect this once-proud program that has hit a nadir with its worst record (4-8 this fall) in 30 years and its second losing season in the last four years.

Wood laughs over the phone and says he “knew something was up” when Riley answered that question about not taking the LSU job — but also not stating he was definitely staying at Oklahoma.

Wood didn’t necessarily expect Riley would be headed to Los Angeles a day later, but he’s not quite as surprised as everybody else.

“As far as my reaction to USC, he’s never afraid of a challenge, put it that way. He’s never afraid of a challenge,” he says. “It doesn’t surprise me — it’s very calculated. He doesn’t do anything that’s not calculated. He’s got a plan.”

That’s what Riley laid out when he delivered the news to his parents.

“I think they were a little surprised initially — the initial shock of it. You do something for seven years at the same place and you’re happy, so I don’t know that anybody necessarily saw it coming,” Riley says. “But I think as we talked through them the reasons and about the opportunity, they were excited. They’ve always stood with me and right there beside me on any of these choices, and I think when I laid if out for them they knew it was something we wanted to do and they were totally supportive.”

That goes for all of his family and friends, he says.

“I think they know me. I’m not someone that’s going to do something without really thinking it through,” he says. “So was there surprise? Sure, there was. But I think people know us and I think they know how much we enjoyed our time at Oklahoma, how great of an experience we had there, so I think they knew if this was something that we felt like was the right opportunity then there must be something really good about it. So everybody’s been very excited, very supportive and hopefully we can convert a few to USC fans now.”

Around Muleshoe, that shouldn’t be a problem.

Riley may not be getting back to town anytime soon to visit the coach’s office at the high school or to pop into Leal’s for lunch, but the mutual attachment between he and his hometown isn’t changing with his move out to Los Angeles.

It’s a part of him, and he’s a part of it.

“I imagine come the fall you’ll see some ‘SC shirts and stuff in town. He’s a good kid. People are proud of him,” Conner says.

“They still follow Lincoln,” Wood says. “If they’re not fans, I sure know that they’re going to be watching them and seeing how they do, looking up USC and seeing if they won. No doubt about it.”

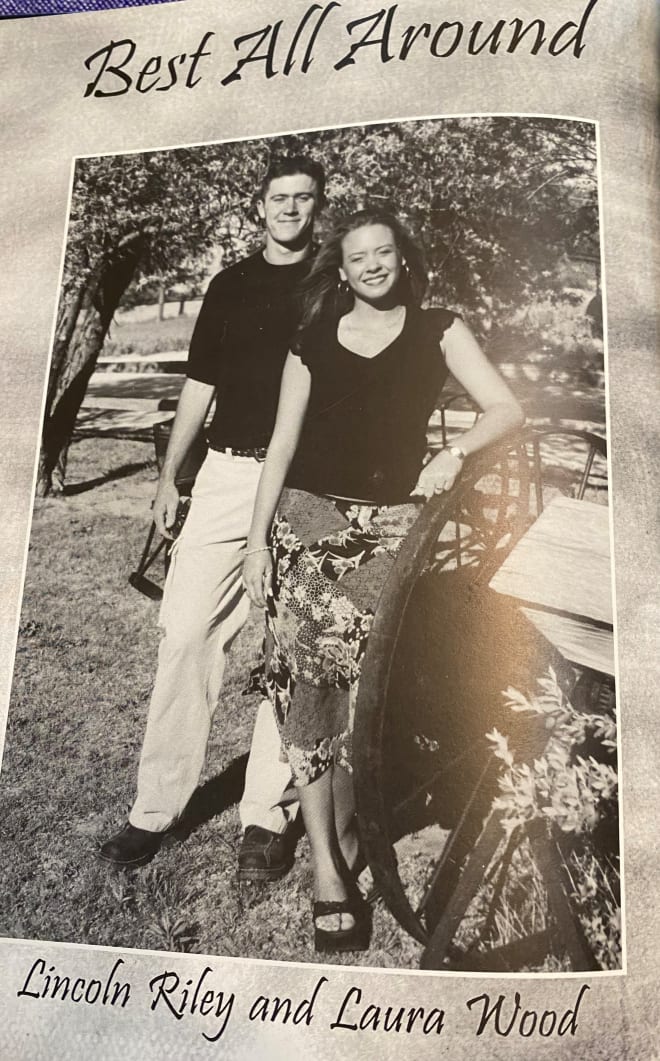

From the Muleshoe High School yearbook. (Muleshoe HS yearbook)

Alice Liles, Lincoln Riley’s junior year English teacher at Muleshoe High School, wearing the shirt from the Mules’ 2000 state semifinals season. (Ryan Young/TrojanSports.com)

Thanks to Ryan Young for sharing his story and pictures with me so I could share them with you.

Great article on Lincoln’s background.

Glad that I was able to share it with everyone.

Cool story, even for someone who’s not a football fan.

Glad you enjoyed it, even if you aren’t a fan, Nola.